All year, my husband and I had been debating whether to take our dog to France. We were invited by his parents to spend the week with them and their miniature schnauzer in their pied-à-terre, and it had been suggested to us that our dog’s presence might be unwelcome, that she would be stressed out by the experience, that she might not get along with the dogs of Greater Nice. That the trip wasn’t that long. That New York has some very fine dog-sitters. That we were traveling, for the first time, with a baby. I found these arguments mostly reasonable. My husband did not.

The issue wasn’t, he insisted, that he didn’t want to leave Sherrie, who is a dog. It was that Sherrie, a dog, didn’t want to be left. In adopting her, we had assumed responsibility for her health and happiness, which would of course be sometimes inconvenient. Dogs’ lives are short, and her best friend (the schnauzer) would be there. “Doesn’t she deserve to have experiences too?” he asked. Of course she does, I thought. But also — and I could not get past this — she’s a dog. I pictured myself sweating in the airport with a crying baby, a dog, and several rolling suitcases and wondered if it would be possible to have one fewer responsibility.

In This Issue

In our own (human) lives, we claim to value “experiences” because it is interesting to do things we normally don’t do, because it imbues life with a sense of possibility, and because it gives us something to talk about at dinner. I thought about a researcher I’d talked to years ago who argued that novelty could be an important part of fun. “When you do something for the first time, or something slightly different from what you used to do, you tend to be more engaged,” he’d told me.

I tried to remember when Sherrie had last done something “for the first time.” She has a good life, I think. She walks at least 10,000 steps a day on a number of scenic strolls. We (try to) let her lead and (try to) stop when she wants to sniff. We let her scavenge wayward pizza crusts, which is certainly not vet-recommended but seems to bring her tremendous joy. We take her to off-leash hours in the park. She has a bed in every room. I am jealous of her life, and if it were my life, I would be bored out of my mind.

What makes a dog’s life rich? To love one is to worry. As their companions and their captors, we have an unsettling amount of control over the quality of their lives, a fact made more complicated by the reality that what is best for them is not necessarily what is best for us.

By most metrics, Mari, a four-year-old black Havapoo, leads an idyllic urban-dog existence. She lives in Brooklyn with a 53-year-old brand strategist named Doug Cameron, his partner, and their toddler and is fed and housed and loved. But Mari was a pandemic puppy, which means she spent her first months with the Camerons gallivanting through the countryside, where she took walks around lakes and scampered up mountains and learned to swim. “In the early days, we kept laughing at how smart she was,” Cameron says. “If we were discussing going outside, she would know.” Now, back in Brooklyn, he and his partner work remotely, and Mari spends her days snoozing under the table during their endless calls. “The learning opportunities have gone down and down and down and down,” he says sadly. “Sometimes I think, Am I letting her mind go to waste?” With Cameron’s 3-year-old daughter, the goal is to expand her horizons all the time: “Learn through the park, learn through your scooter, learn through reading book after book after book,” he says. They don’t think about it that way for Mari. Mari’s experiences are, at best, “secondary considerations.”

I look at my own dog and my daughter, and though I am responsible for both of them, their needs are not the same. As a domestic pet, Sherrie will not need to someday navigate the world alone. She is not responsible for solving its problems. I do not need to instill in her a sense of justice and morality, cultivate a work ethic, or teach her to weather disappointment. At the same time, Cameron points out, “dogs do have this great capacity for development.”

“People assume all that animals need to live well is to be kept free from certain types of harm,” says Jeff Sebo, a philosopher who directs the animal-studies program at NYU and is the co-parent of an 80-pound greyhound-boxer mix named Smoky. But providing animals with food, water, a comfortable living environment, and room to exercise is, as he sees it, “table stakes.” I’ve talked to countless people who told me about how much their dogs appeared to like being in new places, who liked kayak trips and road trips, who had ditched the monotony of kibble for wildly varied diets. The owner of a pit-bull–Lab mix named Evvie told me about batch cooking for his dog, who seems to thrive on culinary newness. “My partner is a really good cook, so she’ll go, ‘Okay, this week let’s do Italian seasoning!’ ‘This week, let’s do Pakistani seasoning.’ We’ll mix it up,” he says. Evvie also has a penchant for exploring unfamiliar real estate. “She really likes going inside people’s houses. She’s very excited to walk around the house for ten minutes and just smell and look around.”

I wrote to Alexandra Horowitz, who runs the Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard and is the author of a small canon of literature devoted to the question of what it’s like to be a dog, to ask whether the species values new and interesting experiences, such as international travel. “Like us, dogs do appreciate novelty. They are interested and engaged in new places, people, things (including toys),” she replied. Also like us, dogs need the “routine and habit and reliability of a certain set of stimuli before they can relax,” she cautioned, but from there, they can begin to expand their universe. Still, “there’s no strict amount of newness that a dog needs or wants — at least, no one has observed or studied that.” In other words, even if I know for a fact that Sherrie prefers not to eat the same food every day, I can’t necessarily use that to draw conclusions about how she’ll take to France.

-

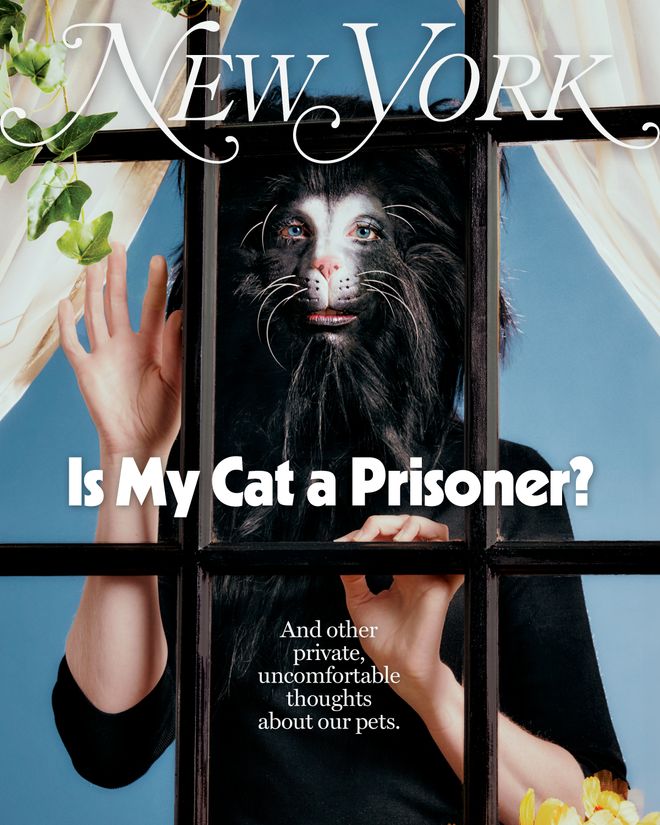

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

-

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

To think about dog experiences is to grapple with one of life’s fundamental questions: What is the point of doing anything? People seek out all kinds of adventures. We travel. We make up excuses to climb rocks. We go to movies, to the theater, to escape rooms. We run marathons; we do psychedelic drugs. These are antidotes to boredom in the present but also an investment in the future. We are, in theory, better people for having soaked up the world around us: more empathetic, smarter, and more curious.

Do adventures offer dogs the same chance at “improvement”? Vanessa Woods, a research scientist at Duke University’s Puppy Kindergarten, recently worked on a project studying the cognitive development of very young puppies. They divided 101 eight-week-old kindergartners, all service dogs in training, into two groups; half were sent home to live normal puppy lives with nice families, while the other half rotated between three to five different parents, all Duke undergrads. They slept in dorm rooms, went to the dining hall, studied in libraries, hung out in common rooms. They volunteered in hospitals. Some went on trips. “We wanted to optimize the experiences they would have, both social experiences and just day-to-day,” says Woods. “We were really trying to just think of the craziest Disney World for Puppies that we could create.” Every two weeks, the dogs were tested with cognitive puzzles. “What we found,” she tells me, “was that creating this intensive experience for these puppies did absolutely nothing.” Their scores were exactly the same as the control. This at least suggests that the puppies’ abilities were not fundamentally altered in any lasting way by their blitz of on-campus experiences.

Then again, self-improvement is not the only reason to seek out adventure. Even if their undergraduate rumspringas didn’t make the puppies better learners, did they perhaps enjoy themselves more in the moment? A few years ago, I went snorkeling for the first time and loved it, and I especially loved the fact that I loved it, which felt off-brand, and now I walk through the world knowing this unlikely fact about myself: Despite all outward appearances, I am the kind of person who loves snorkeling!

If Sherrie went snorkeling and loved it, would she carry it with her as an episode in the story of her life? It’s true that dogs don’t have the language to “frame, ponder, and store away” experiences, which is often what we mean by making “memories” — the same reason, Horowitz notes in Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know, that humans don’t have true memories before the age of 3 — but that doesn’t mean dogs don’t remember. They remember all kinds of things, obviously: whom they know, where they live, the routes they walk, which coffee shops give out biscuits. My dog will probably not, three years from now in Brooklyn, bask in the sun-drenched memory of that one time she met a real French bulldog in Nice, but can we absolutely rule it out? “I don’t know,” says animal field biologist Marc Bekoff, the co-author of Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible. “For all my years of doing this, I’m very, very hesitant to say an absolute ‘No, dogs don’t miss a particular experience.’ ”

The trouble, several researchers warned me, is that once we recognize that dogs do desire novel experiences, our human biases and frameworks can lead us astray. As their guardians, we might, for example, “assume that they’re more like us than they are and that they find the same things pleasurable as we do,” Sebo tells me. Elizabeth Schneider, a 32-year-old on Long Island, has driven long distances to take her still-spry senior spaniel mix, Rory, on a hike. She is trying to give Rory the best possible life but has asked herself, Am I doing these things more for me than I’m doing them for her? “It’s gotten to the point where we’ll be at the base of the mountain and she will refuse to move,” she says. The experts I spoke to agreed that a rich canine life doesn’t necessarily require capital-E Experiences, like witnessing the northern lights or skydiving. To a dog, something as mundane as a walk could feel novel in itself. “For an olfactory creature, what looks like the ‘same path’ may have been rewritten overnight with odors left from dogs, people, and other animals,” Horowitz pointed out. Endless loops through the same neighborhood may be quite exciting for Sherrie. She is fully engaged, interminably sniffing tree pits. I’m the one who’s bored.

For all that we don’t know about canine cognition, Bekoff says, dogs are not black boxes: “If you pay careful attention to their behavior, they’re telling you when they need something.” Sherrie, I realized, often makes herself and her desires very clear. The problem is I don’t always want to hear it. I want to have cinematic adventures with my dog; she wants to go scavenging outside the Chick-fil-A in Downtown Brooklyn. “You’ve got to know your dog as an individual,” Bekoff urges. “When dogs have the ability to express their dogness, they’ll tell you when they want some novelty in their lives.”

At the risk of projection, I believe Sherrie does seem to enjoy conventional adventures. She bounds through the park and scrambles up rocks and has a particular affinity for sand, and while she has not historically loved the acute experience of being in transit, she seems energized by the prospect that something interesting is happening for once, finally, thank God. As for whether she’ll be happy in France, I suppose we’ll find out. She will spend the week with her best friend, the bicontinental schnauzer. The bread is very good there. She will be with her family. “I think a lot of times, our dogs just want to be with us,” says Lori Kogan, a psychologist at Colorado State University focused on human-animal interaction. My dog may not care if we go on vacation or spend the day pacing back and forth along the Gowanus, but I am happier and more relaxed on vacation, more giving, more patient, less preoccupied by my phone. Doesn’t my dog deserve me at my best? And am I not, like all of us, at my best on the French Riviera?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like …

➭ Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

➭ Are We Lying to Ourselves About Emotional-Support Animals?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?