In 1990, Congress passed the Americans With Disabilities Act, which, among other things, defined who and what service animals are: They must be either dogs or miniature horses, and they have to be specially trained to do tasks that help someone with a disability.

The ADA makes it clear that “dogs whose sole function is to provide comfort or emotional support” are not service animals. But Americans have largely ignored that, opting instead to give emotional-support animals the same authority, official-looking vests and all. ESAs, though, are not much different from the average pet. They have no special training and possess no unique skills. They can be peacocks or ferrets or really any pet at all. The only thing that distinguishes them is a letter from a mental-health professional testifying that their presence helps someone with a psychiatric disorder. Armed with that, ESAs can live with their owners in dorms, sneak into a condo with a no-pets policy, and, until recently, ride in the main cabin on airplanes.

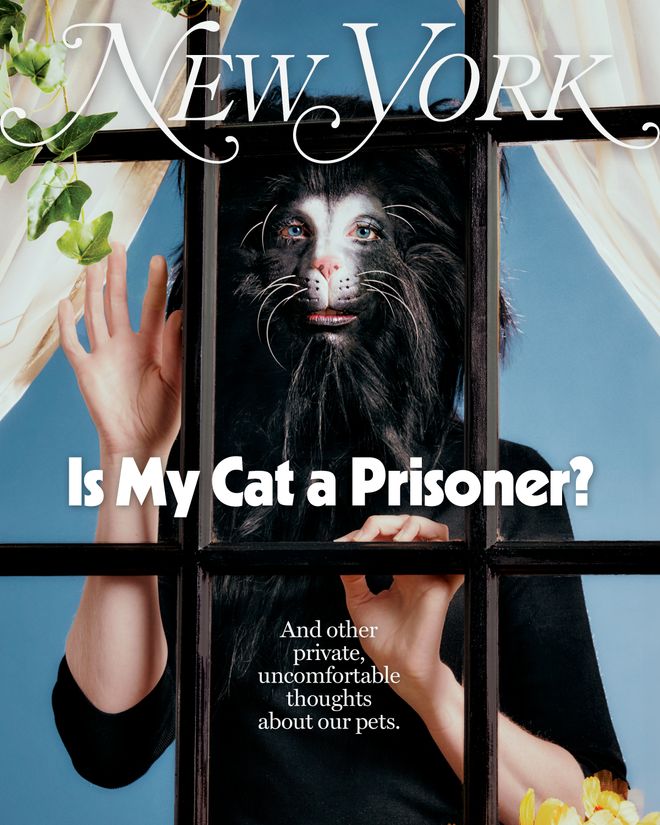

In This Issue

One study found that between 2002 and 2012, the number of ESAs in California increased by 1,000 percent. In 2015, the National Service Animal Registry registered more than 65,000 ESAs. Today, it has more than 240,000. From 2017 to 2018, United Airlines reported a 75 percent increase in ESAs. Around the same time, Delta saw an 84 percent rise in problems with animals, including biting, peeing, and pooping on flights. “The number of people who have an emotional-support animal so they can have a pet in an area where they otherwise wouldn’t be able to is absolutely obscene,” says Dr. Elaine Sheikh, a veterinarian in Michigan.

In some ways, the ESA is a formalized version of our emotional bond with our pets. At the end of a long day, it’s a relief to find their furry, unconditional love waiting for us. But as the veterinarian Dr. Maria Solacito points out, we often end up grafting our neuroses onto animals. “Your pet feeds off the energy you put out there,” she says. Dogs in particular are adept at reading human emotions. Recently, Solacito saw a client who burst into tears because she wasn’t allowed to quarantine with her sick dog, who reacted by howling throughout the visit. There’s even research that suggests people with separation anxiety are more likely to have dogs with separation anxiety. Sheikh also points out that because ESAs never have to be separated from their owners — they don’t have to wait outside the grocery store or be kenneled while their owner goes on vacation — they’re often the worst-behaved pets she encounters.

Vets don’t certify ESAs, but Sheikh wonders if some species are, in fact, constitutionally unable to provide the support we crave. She’s seen bunnies with ESA certification, something she finds ironic given that when stressed, bunnies can have heart attacks and die. “I love bunnies,” she says, “but your bunny is not helping you.”

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like …

➭ Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

➭ Does My Dog Hate Bushwick?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?