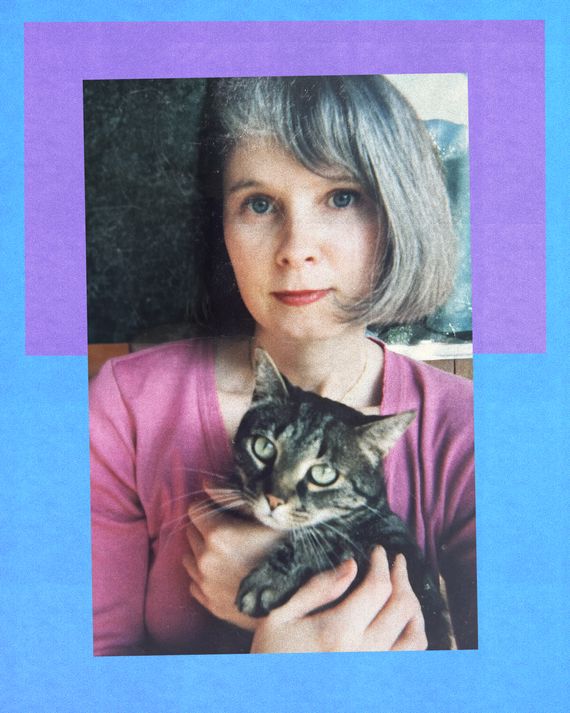

One day in 1991, I thought about taking my healthy six-year-old cat to the ASPCA, where she would almost certainly have been “put down,” a.k.a. killed. I had adopted Suki when she was six months old and lived with her lovingly until a dramatic upheaval caused us to be (almost literally) at each other’s throats. After nearly two months of animosity, I’d reached a breaking point: She would have to go. That I would seriously consider doing this to a beloved pet revealed me to myself in a way that still gives me pause. It is remarkable how a relationship with an animal can do that.

I grew up having cats as pets, but I didn’t really own one as an adult until the age of 30; my circumstances were too unstable, and the few attempts I’d made as a teenager to adopt the cats that had shown up in my life didn’t end well. When I moved to Manhattan in my 20s and finally found a place to live, it was a tiny studio that I deemed too small for a cat to live in with any satisfaction. It would be, I thought, unfair to put an animal in that situation.

But then this cat showed up. One day in the spring of ’85, I was walking down 8th Street when I heard loud meowing — to my surprise, it seemed to be coming from a parked car surrounded by a small crowd of people who were looking under the body and the hood. As I came closer, someone said, “There it is!” before pulling from deep under the hood a limp, very shocked, loudly crying adolescent tabby cat. Because the driver of the car had no idea where the little cat had come from, because no one else volunteered, and because I lived close by, I offered to provide her with temporary shelter (plus vet care; her paws were burned) and find her a home. But the latter proved near impossible, and during the time it took to realize that, Suki and I had bonded. She was wonderfully intelligent, full of energy and play but also tenderness and desire for affection. And she seemed to be very comfortable in my studio.

In This Issue

Still, I adopted her with reservations in part because of my strange schedule; I often worked a graveyard shift that sometimes lasted 12 hours, and I couldn’t afford to turn down the work when it came. On the flip side, because the job was freelance, I would get several days off at a time. I thought it could work out.

And it did, sort of. When I could be there for her, Suki was happy enough — but as she grew bigger, the small space chafed, particularly during those long shifts. I would sometimes come home too exhausted to play with her for longer than 20 minutes or so, then lie in bed trying to sleep while she rocketed around the room and over my body, knocking stuff down, batting at my nose until I was so aggravated that I got up and yelled at her, then tossed her in the bathroom and closed the door.

To give her some variety, I let her roam in the hall when the super wasn’t around and tried taking her out for walks in a harness that she didn’t like. It was stressful, and I felt real guilt about frustrating her natural wants. One particularly awful time, I was especially desperate to sleep and she was especially desperate to charge around the room; I so lost my temper that I actually slapped her, causing her to race up into the space above my closet to hide. I got back into bed but couldn’t sleep because I felt wretched for hitting her. My wretchedness lasted for maybe five minutes before Suki came blasting down from her perch, charged back and forth over me, knocked something down, then jumped up on the bed, batted my nose and looked at me like, “Bitch, what are you gonna do about it?” I felt such admiration and delight that I laughed! I petted her, let her play with and bite my hand a little; after that, I guess she’d blown off enough steam to sleep because she lay down next to me as usual.

While it was rocky at times, there was respect and affection; we gave each other happiness. But it also felt like we were in an ongoing, often tense negotiation with each other regarding space and need. In this negotiation I certainly had the most power. But it would be a mistake to say that Suki, a remarkably strong-willed little creature, had none. I’m thinking of the time when I was so sick that I couldn’t get out of bed except to feed Suki or use the bathroom; during that time, she did not run around the room or swat my nose even once. She stayed next to me — until one morning when she sniffed me, realized the fever had broken, and smacked my nose, meaning, “Okay, ass out of bed.”

In 1987, I sold my first book, and we later moved to Marin County in California. The place was an in-law cottage that looked like a renovated barn. It was located in a beautiful canyon. It was at least three times as big as my studio had been, with sliding glass doors that opened onto a deck looking out into a ravine full of greenery and wildlife. Suki was very pleased — she made that plain with her ecstatic facial marking of every corner and her purring, full-bodied rubbing on my legs. I was cautious about letting her out at first, but when I finally did, her happiness was complete. Because I now worked at home, I was with her much more of the time, so in addition to the outdoors, she had more frequent playtimes with me. She no longer woke me up with frenetic racings around or attacked my nose. She also stopped getting the cystitis which had plagued her the entire four years we had lived in the Manhattan studio.

It was lovely and then — I made a mistake.

I had been thinking about getting a kitten, wondering if it would make Suki even happier or … not. Then one serendipitous afternoon, a woman walked up to me on the street with a cardboard box. She said she had found a kitten on the side of the road and couldn’t adopt it: Did I want it? This was obviously a sign! I brought the kitten — a tiny orange male — home on the spot.

Suki took one look at the newcomer and hated him. She never hurt the kitten, whom I named Honus, but she cursed at and menaced him constantly, rising above him with one paw ready to strike. She cursed at and menaced me constantly, not even allowing me to touch her. I wasn’t shocked by this. But I expected her to calm down eventually. And she might have if she’d had more time. In a few weeks, I was due to leave town for a professional trip for nearly a month. In the week before I left, I was encouraged to see her show some curiosity toward Honus; she also softened toward me, letting me pet her a little. Feeling optimistic, I arranged for a pet sitter named Barbara to stay at the house during my absence.

It went wrong almost immediately. With every call home I made, the situation seemed to have gotten worse. “I’m afraid of Suki,” said Barbara. “I’m afraid to get out of bed in the morning—she’s circling the bed like a shark.” I found this description so bizarre that I decided Barbara must be at fault. Then Suki began attacking Barbara, swiping at her legs.

I was about to get an early ticket home when there was another development: Barbara woke one morning to find that Suki’s face was horribly swollen. My poor cat had a tooth infection, meaning she’d been in pain for some time and needed surgery. Suki had to spend at least a week at the vet prior to and after the procedure; by the time she was ready to come home, I was due to arrive in a matter of days. Barbara reported that on her return the cat was subdued and unfriendly but not especially aggressive. I was relieved; I was also confident that with the infection gone and me present, all would eventually be well.

And at first, that seemed possible. When she’d left, Barbara had let Suki out, and I started calling her as soon as I emerged from the taxi. I didn’t have to wait long before she came bounding out of the underbrush like Lassie, rubbing against me, almost leaping into my arms. But as soon as we entered the house and she saw Honus, she began snarling. I quickly set her down; she glared at me with pure animal rage and bolted out the door.

She did not come in again until mealtime, when she scarfed her food, snarled at me, snarled at Honus, and bolted out again. When she came back in for breakfast, I tried to sweet-talk her, by which I mean I attempted to sit with her and tell her how much I loved her and wanted this to work out. But she would not sit with me, so instead I followed her around, futilely declaring my good intentions while she either ignored me or growled. When I tried to make her sit still and listen, she swiped at me and drew blood. Meanwhile Honus was delightful, playing with me and cuddling by day, sleeping close to me at night. It became easy for me to just about ignore Suki except to let her in and feed her, then let her out where she stayed all night.

-

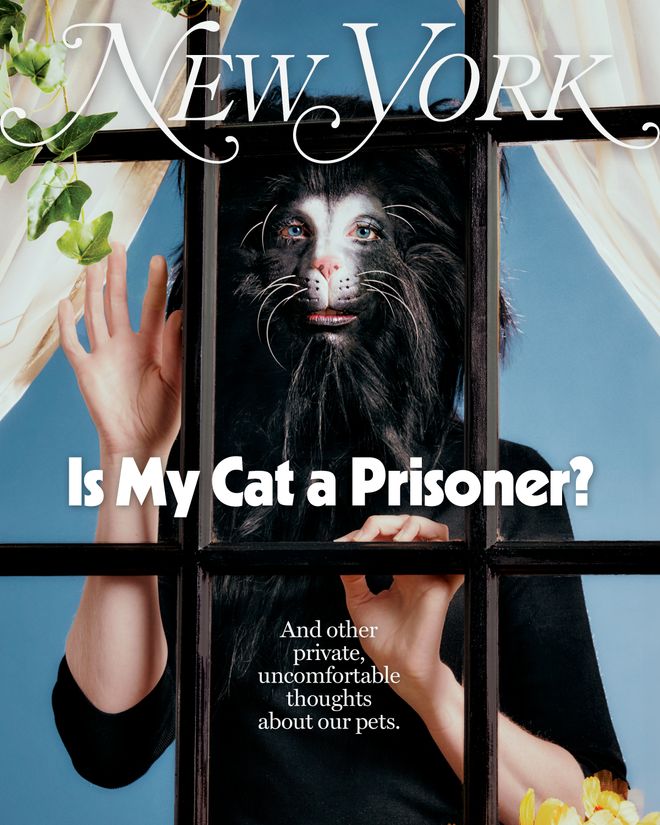

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

-

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

One night, during a thunderstorm, my conscience woke; like many animals, Suki was afraid of storms, so I put my boots on, got an umbrella, and went out to call her. I found her sheltering under my neighbor’s car. For several moments I crouched there, entreating her to come in. She stayed put, hissing at me. After that night, I tried keeping her in again; she reacted by attacking me, actually charging me and swiping with her front paws — and sometimes she connected. Her fury was several times bigger than her body, and I was becoming angry in response — very angry. The last time she struck out at me, I got down on the floor and said to her, “If you hurt me, I will kill you. I don’t want to do that. But if you really hurt me, I am going to kill you.” She could not have understood my words, but I am sure she understood my message. She flattened her ears against her head and, pupils dilated, hissed with teeth fully exposed as if to say, “If I could, I would kill you right now” and then went for the door. I opened it for her.

Around this time, I called the vet and asked him if he thought there was anything I could do to improve the situation. He told me that the only way was to remove the kitten — or Suki. He said Suki had probably developed the tooth infection right around the time Honus arrived and that the stress of my leaving had likely made it much worse; he thought she had associated the increasingly terrible pain and the disruption of her home with the kitten and that there was no way to reverse that.

I had to choose between an enraged middle-aged cat who hated me versus an adorable kitten who loved me or at least acted that way. The more I thought about it, the more natural it seemed to … end the misery. I couldn’t believe what I was thinking of doing: taking Suki to the ASPCA, where she would almost certainly die. I remember saying to someone, “If a person acted toward me the way that Suki has, I wouldn’t tolerate them in my home either.” Of course the person said, “Yes, but you wouldn’t have them killed.” And I wouldn’t, not only because I couldn’t (at least not legally) but because for most people (and for me) to essentially kill a member of our own species is a profoundly wrong act that not many of us are going to commit just because we don’t like certain behavior.

But an animal is in another category. Since infancy, we are brought up to see them as less valuable than we are even if we love them; in that way we are very like … other animals. Animals generally prefer their own species. How often does an animal feel morally compelled to show a weaker species consideration? No natural predator hesitates, when hungry, to kill another species for food or, in the case of cats, for pleasure. Part of the reason we feel superior is our very real capacity to choose to act differently. But our connection with animals reminds us of that more fundamental, less moral way of being. As predator or prey, animals are always closer to the reality of killing than we are, and on a very subliminal level, their proximity brings us closer too.

None of that made what I was contemplating any less cruel. What pulled me back from the brink of this awful choice was not an appeal to abstract ethics. It was an appeal to my own well-being — which I’d somehow forgotten was linked to Suki’s. I told a close friend that I had just about made up my mind to take my old cat to the ASPCA for being too mean. She was silent for a long moment. She said, “I hope you reconsider. You’re really mad at Suki right now, but you love her. If you take her there and she’s put down, I don’t think you’re going to be able to live with yourself.”

As soon as she said it, I knew she was right; it was as if her words awakened me from a trance of ruthlessness. At first, I was not happy about it. My decision was made easier when Barbara said she would love to adopt Honus. Miserably, I removed his food dishes; miserably, I vacuumed his fur off the rug. When dinnertime came, I let Suki in. The house probably still reeked of Honus, and she didn’t behave very differently at first. But slowly she realized the intruder was gone. On our first evening, she didn’t demand to go outside; she didn’t sleep with me or show me any affection, but she didn’t hiss or snarl either. I didn’t try to pet her; I watched and waited to see what she would do.

The next evening I found out. She had just eaten and had not asked to go outside. I was sitting on the couch watching TV. For the first time in maybe two months, she jumped onto the couch with me. I said, “Hi, Suki.” She groomed herself for a few minutes. And then she languorously stretched her body and came into my lap. To my delight, she responded to my petting with unreserved purring. Our bodies synced and relaxed; she soon fell deeply asleep as I blissfully watched the tube. At one point some unexpected noise woke her with a start; she looked up at me with an expression of great relief. She then put her head back down, sighed, and stretched her forepaw out on my leg, gripping my pants with her claws as if to say, “Mine. All mine.” It was true. Honus was a lovely kitten, but Suki was my cat and I was her person. Regardless of who had more power, our well-being was inextricably linked. In some impossible-to-define psychic sense, we were, at that moment, equal.

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like …

➭ Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

➭ Are We Lying to Ourselves About Emotional-Support Animals?

➭ Does My Dog Hate Bushwick?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?